5 Tips for Becoming a Source of Sureness

Uncertainty is an inevitable part of our daily working lives in the Admissions Office. This article aims to provide insight into sources of uncertainty and give tips on how to stay on top of it, in order to help families make mindful decisions.

In Admissions, we regularly encounter situations of uncertainty and aimto provide stability in the midst of a highly uncertain external and internal environment. At AISB we have seen how a deeper understanding of our roles and the scenarios we influence can positively impact our outcomes.

The simplest problem is a lack of information, when, for example, a family inquires about our school or the application process. Kamal and Burkell (2011) call this internal uncertainty.

The more complex, external uncertain situations arise when both possible outcomes and their probabilities have yet to be determined. (Kamaland Burkell, 2011). Relocation understandably causes great uncertainty, a circumstance the majority of our applying families encounter. As well, transitioning families are often relocating from a variety of differing cultures.

On the Admissions side, we need to retrieve information from hundreds of families in order to keep enrollment figures up to date. In addition, these figures are continually changing.

In order for us to provide the best support we can, we must maintain the highest possible level of certainty. If we can communicate as we intend to, we have already accomplished a great deal. Here are five ideas that can help to maintain certainty:

1. Be clear and certain in your communication. Do not leave room for second guessing.

“Clear is kind. Unclear is unkind.”

Brene Brown

Humans can only handle limited uncertainty. Thus, when people lack clear information, they tend to fabricate a false certainty by creating shortcuts. These shortcuts are sometimes referred to as cognitive biases. In New Scientist, the article “Get Smarter” (2015) explains that “There are good reasons why such biases are embedded in our psyches. They have evolved to help us make quick decisions with limited information and difficult decisions with a large amount of hard to assess information.”

The anchoring effect is “our tendency to rely too heavily on the first piece of information offered, particularly if that information is presented in numeric form, when making decisions, estimates, or predictions” (Yagoda, 2018). It is vital that we are clear and consistent in our communication with families. Even if the information may not be comfortable for the family to hear, it is better to ensure it is understood from the beginning.

2. Look at your online context and make it user friendly.

“Make every interaction count, even the small ones. They are all relevant.”

Shep Hyken

We must become clear about the fact that cognitive biases affect us. Projection bias is “the assumption that everybody else’s thinking is the same as one’s own” (Ryan, 2017). By practicing our empathic skills and putting ourselves in the place of others, we can create a user experience for our families that suits their level of uncertainty and hence their particular need for information.

3. Determine what the family thinks and believes.

“What stands in the way becomes the way.”

Brene Brown

According to Yagoda (2018), confirmation bias is “the effect that leads us to look for evidence confirming what we already think or suspect, to view facts and ideas we encounter as further confirmation, and to discount or ignore any piece of evidence that seems to support an alternate view”.

As David Willows (2019) has suggested, we need to ensure that our communication with families asks for more than it explains. We can only have meaningful conversations with families when we learn their thoughts and beliefs. We admissions professionals need to disengage from our point of view and position ourselves into theirs.

4. Build your cultural intelligence.

“Experiencing different cultures is one of the best things a human being can do.”

Stephanie Gilmore

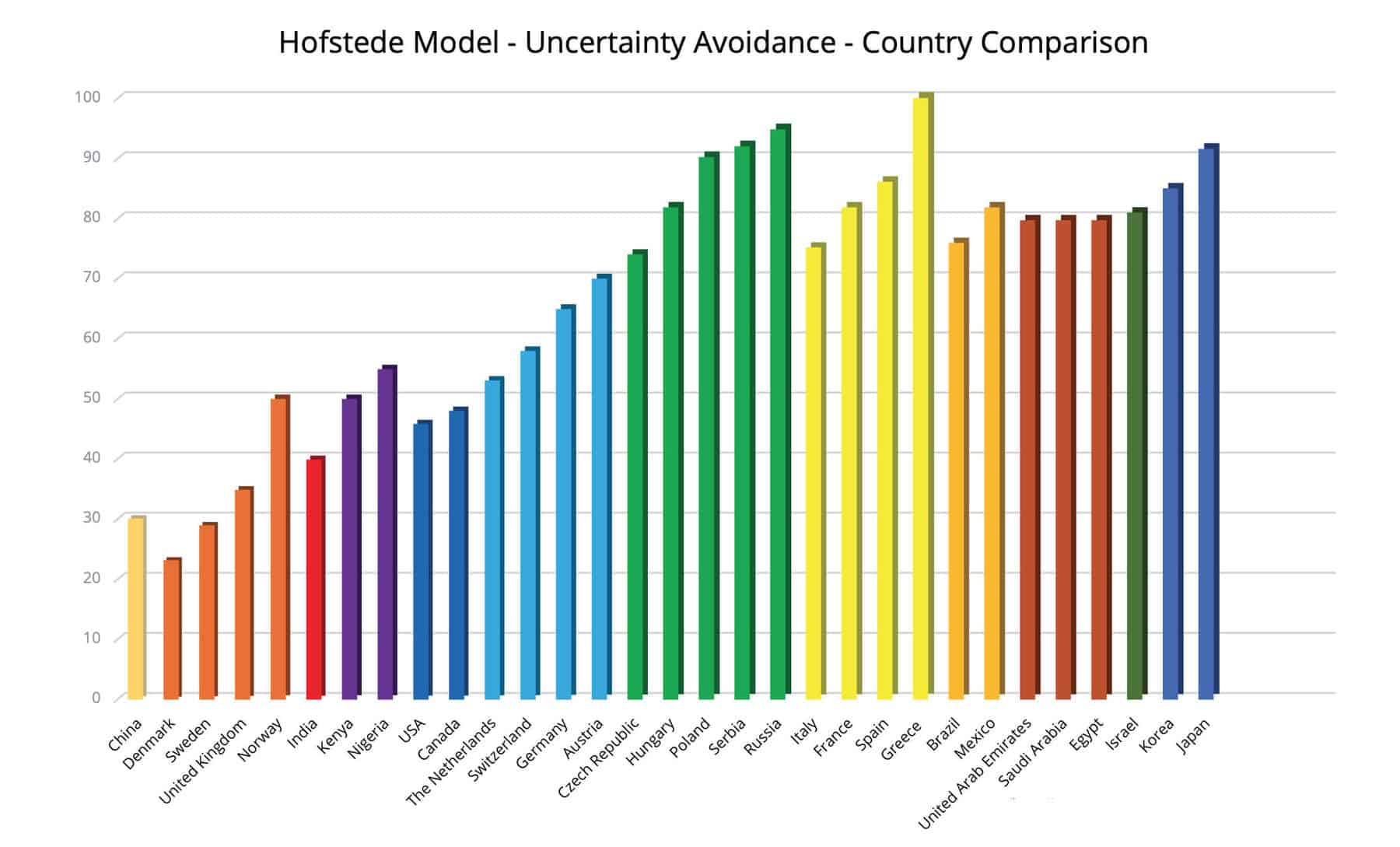

Meeting families from various cultures is a blessing of our profession. At the same time, however, it is a continuous challenge. The way different cultures cope with uncertainty varies a great deal as well. Professor Geert Hofstede has studied six dimensions of national cultures, one of which is uncertainty avoidance.

“The dimension Uncertainty Avoidance has to do with the way that a society deals with the fact that the future can never be known: should we try to control the future or just let it happen? This ambiguity brings with it anxiety and difffferent cultures have learnt to deal with this anxiety in difffferent ways. The extent to which the members of a culture feel threatened by ambiguous or unknown situations and have created beliefs and institutions that try to avoid these is reflflected in the score on Uncertainty Avoidance.” (Hofstede Insights, 2019).

The table shows clusters of countries’ Uncertainty Avoidance scores.

Source: Hofstede Insights

China has one of the lowest scores at 30. As the model (County Comparison, 2019) describes, the Chinese are comfortable with ambiguity. Adherence to laws and rules may be flexible to suit the actual situation and be addressed pragmatically.

The United Kingdom and the Scandinavian countries also have low scores. In these countries, the end goal is clear, but the details of getting there are fluid and flexible. Nationals from these countries tend to speak clearly when they are in doubt or do not know something.

Among North Americans there is a fair degree of acceptance for novelty; they are often willing to attempt something new or different. North Americans do not typically require fixed rules and are less emotionally expressive than higher scoring cultures.

Countries with high scores generally maintain rigid codes of belief and behaviour and thus tend to be intolerant of unorthodox ideas. In these cultures, there is an emotional need for rules: time is money; people are driven to be busy and work hard; precision and punctuality are the norm. Innovation may be resisted and security is an important element in individual motivation.

In order to stay abreast of cultural awareness and gain confidence in dealing with families from different cultures, make sure you create occasions where you can casually interact with parents at your school. Make time to attend parent events and participate in activities with them. It can sometimes be challenging to spend time away from the Admissions Office, but the investment is well worth it.

5. Help families to make good decisions by reinforcing the most important messages.

“People don’t buy what you do; they buy why you do it. And what you do simply proves what you believe.”

Simon Sinek

As David Willows (2019) suggests, be clear about the deep understanding you want every family to have. Focus on that, discard unimportant information, and continually reinforce what is important. There should be no doubt about the fact that Advancement has the broadest overview of our school story and identity. This knowledge compels us to convey our school’s essence, which will then help our applying families make considered decisions about the schooling of their children.

We Admissions professionals understand how families from different backgrounds and cultures typically react, which type of questions they ask, and what their beliefs about schools and school systems are. This accumulated knowledge is an asset we can build upon to use as our foundation for providing the best possible experience for each family turning to us for support. In the end, our mission is to provide responsive, efficient and exceptional service to families through the admissions cycle.

Get Smarter. (2015 January). New Scientist, 228(3051), 30-39.

Yagoda, Ben (2018, September). Your Lying Mind The Atlantic 322(2) 72-80.

Ryan, M. Brendan (2017, February). Kahenman and Tversky’s Research on Heuristics and Its Application to Junior Athletic Development and the College Recruiting Process Higher Education Studies 7(2), 23-26.

Calamaras, R. M., Tone, B. E. (2012, July). A Pilot Study of Attention Bias Subtypes: Examining Their Relation to Cognitive Bias and Their Change Following Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. Journal of Clinical Psychology 68(7), 745-754.

Kamal M.A., Burkell J. (2011, December). Addressing Uncertainty Canadian Journal of Information & Library Sciences, 35(4) 384-396.

Let’s think about cognitive bias. (2015, August). Nature, 526(7572), 163-163.

Gill, Cassandra (2017, March). Hofstede’s cultural dimensions and differences across cultures.

Retrieved from: https://blog.oup.com/2017/03/hofstede-cultural-dimensions/

Hofstede Insights – Uncertainty Avoidance Dimension retrieved from: https://www.hofstede-insights.com/ Hofstede Insights – Country Comparison Retrieved from: https://www.hofstede-insights.com/country-comparison/

Willows, David (2019) Admissions and the Illusion of Transparency. Retrieved from>: https://www.fragments2.com/blog/2019/6/19/school-admissions-and-the-illusion-of-transparency

All Services

All Services